Gene anàlisi d'enriquiment conjunt és un dels molts enfocaments per a la l'anàlisi de l'expressió gènica dades del perfil i es descriu en un paperdels treballadors a l'Institut Broad.

Gene anàlisi d'enriquiment conjunt és un dels molts enfocaments per a la l'anàlisi de l'expressió gènica dades del perfil i es descriu en un paperdels treballadors a l'Institut Broad.

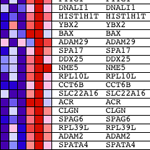

El concepte bàsic va ser motivada per l'observació que l'estudi de gens individuals que mostra la diferència més significativa en el nivell d'expressió entre dos estats o fenotips és mancada d'una visió mecanicista. En lloc, té més sentit per prendre una conjunt de gens compartir algunes vincle biològic, i fer la pregunta - no tot el conjunt va mostrar estadísticament important enriquiment en aquells gens que tenen expressió diferencial?

La conjunt de gens pot ser elegit, a priori, per a un nombre de raons v.g.. el conjunt de gens coneguts per estar influenciada per sobre- o sota l'expressió d'un micro-ARN, o potser un conjunt escollit basat en la ubicació cromosòmica, o gens per als quals la funció molecular, component cel · lular i / o el procés biològic s'han assignat mitjançant els vocabularis controlats de la Ontologia de Gens.

Un avantatge de la GSEA enfocament és que és possible incorporar la seva conjunt complet de dades, no només les transcripcions amb un llindar d'expressió diferencial triat arbitràriament. Estic segur que moltes persones que llegeixen això estaran pensant - "Com pot estar bé per utilitzar el conjunt complet de dades? Normalment jo només consideraria gens amb >2 (O un altre valor preferit)-l'expressió diferencial vegades. "La raó és vàlida l'aproximació és que els gens expressats en nivells baixos o amb gran variació entre les rèpliques no contribueixen a la principal mètrica utilitzada per GSEA, el 'enriquiment Resultat' (ÉS).

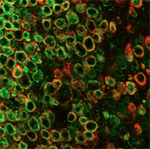

GSEA treballa per primera classificació el valor de l'expressió de cada gen per senyal a soroll relació - el càlcul de la diferència entre els valors mitjans per a les mostres que representen cada fenotip i ajust a escala per la suma de les desviacions estàndard. Això significa que els gens amb grans diferències en el nivell d'expressió entre els diferents estats i poca variació entre repeticions biològics es classifiquen altament.

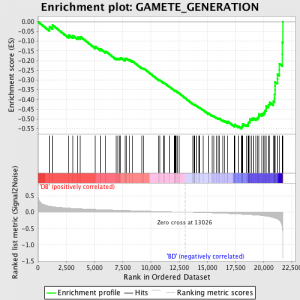

El següent pas és que l'ES, l'estadística primària generada per GSEA, es calcula per a cada conjunt de gens - en el manual d'GSEA, que documenta el programari excel · lent, s'afirma:

"Tots els gens es classifiquen primer per la seva relació senyal-soroll, llavors l'ES es calcula "caminar" per la llista ordenada de gens creixent 01:00 funcionament de summa estadística quan un gen es troba en el conjunt de gens i decreixent quan no és. La magnitud l'increment depèn de la correlació del gen amb una fenotip. L'ES és la màxima desviació de zero trobada en peu la llista. La positiu ÉS indica enriquiment conjunt de gens en el superior de la llista de classificació; 01:00 negatiu ÉS indica enriquiment conjunt de gens en el fons de la llista de classificació ".

Els valors són ÉS normalitzat sobre la base de gen grandària del conjunt i després un la taxa de fals descobriment es calcula, per donar una probabilitat estimada de falsos positius. GSEA utilitza un valor predeterminat molt relaxat 25%, que és adequat per a la generació d'hipòtesis amb un nombre relativament gran de repeticions biològica.

Els científics que treballen en les dades de non-human mostres poden seguir utilitzant GSEA, però caltenir cura - La símbols de gens utilitzats per GSEA són "traduït"De la seva I.E equivalents humana. identificadors utilitzats per als gens de les seves espècies d'interès representat al microarray es converteixen en símbols per a la seva ortòlegs humans, a continuació, s'utilitza en l'anàlisi. Subramanian i col · legues reclamar que aquesta conversió té poc o cap efecte sobre la utilitat de GSEA; s'ha utilitzat amb èxit en múltiples espècies no humanes, però, és clar, això s'ha de tenir en compte en la investigació de resultats en detall.

Per a una excel · lent, a fons, revisió d'eines via, consultar:

Una altra bona font de consells sobre la via d'anàlisi, especialment per a aquells que estan familiaritzats amb el paquet estadístic R és aquí.

Altres lectures