Análisis conjunto de genes de enriquecimiento es uno de muchos enfoques para la El análisis de la expresión génica datos de perfil y se describe en un papelde los trabajadores en el Instituto Broad.

Análisis conjunto de genes de enriquecimiento es uno de muchos enfoques para la El análisis de la expresión génica datos de perfil y se describe en un papelde los trabajadores en el Instituto Broad.

El concepto básico fue motivada por la observación de que el estudio de genes individuales que muestra la diferencia más significativa en el nivel de expresión entre dos estados o fenotipos se carente de una visión mecanicista. En lugar, tiene más sentido para tomar una conjunto de genes compartiendo algunas vínculo biológico, y hacer la pregunta - ¿el conjunto mostraron estadísticamente enriquecimiento significativo en los genes que tienen expresión diferencial?

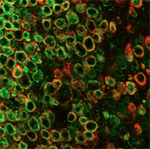

La conjunto de genes puede ser elegido, a priori, por un número de razones p.e.. el conjunto de genes que se sabe están influenciados por encima- o expresión insuficiente de un micro-ARN, o tal vez un conjunto elegido basado en la localización cromosómica, o genes para los que la función molecular, componente celular y / o biológico han sido asignados utilizando los vocabularios controlados de la Gene Ontología.

Una ventaja del enfoque GSEA es que es posible incorporar su conjunto completo de datos, no sólo las transcripciones con un umbral diferencial de expresión arbitrariamente elegido. Estoy seguro de que muchas personas lean esto pensarán - "¿Cómo puede ser correcto utilizar el conjunto completo de datos? Normalmente yo sólo consideraría genes con >2 (O valor preferido otro)-la expresión diferencial veces ". La razón es válida la aproximación es que los genes expresados en niveles bajos o con gran variación entre repeticiones no contribuyen a la métrica principal utilizado por GSEA, el 'enriquecimiento de puntuación' (ES).

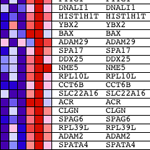

GSEA trabaja por primera clasificación el valor de la expresión de cada gen por Señal a ruido ratio - calculando la diferencia entre los valores medios para las muestras que representan cada fenotipo y ajuste a escala por la suma de las desviaciones estándar. Esto significa que los genes con grandes diferencias en el nivel de expresión entre los diferentes estados y poca variación entre repeticiones biológicos se clasifican en muy.

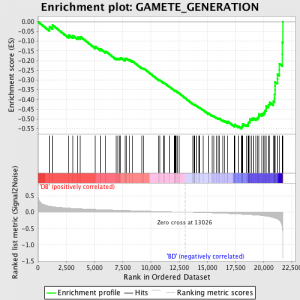

El siguiente paso es que el ES, la estadística primaria generada por GSEA, se calcula para cada conjunto de genes - en el manual de GSEA, que documenta el software excelente, se afirma:

"Todos los genes están clasificados primero por su relación de señal a ruido, entonces el ES es calculado por "caminar" por la lista ordenada de genes creciente un funcionamiento de suma estadística cuando un gen está en el conjunto de genes y decreciente que cuando no está. La magnitud del incremento depende de la correlación del gen con una fenotipo. La ES es la máxima desviación de cero se encuentran en la lista de caminar. La positivo ES indica enriquecimiento conjunto de genes en la top de la lista de clasificación; un negativo ES indica enriquecimiento conjunto de genes en la fondo de la lista de clasificación. "

Los valores son ES normalizado basado en el tamaño conjunto de genes y, a continuación una tasa de falso descubrimiento se calcula, para dar una estimación de probabilidad de falsos positivos. GSEA utiliza un valor predeterminado de muy relajado 25%, que es adecuado para la generación de hipótesis con un número relativamente grande de repeticiones biológica.

Los científicos que trabajan en los datos de no humano Las muestras pueden seguir utilizando GSEA, pero necesitantener cuidado - La símbolos de genes utilizado por GSEA son "traducido"Es decir de su equivalentes humanos. identificadores utilizados para los genes de sus especies de interés representado en el microarray se convierten en símbolos para su orthologues humanos, entonces se utiliza en el análisis. Subramanian y colegas reclamar que esta conversión tiene poca o ningún efecto sobre la utilidad de GSEA; se ha utilizado con éxito en múltiples especies no humanas, pero por supuesto esto debe tenerse en cuenta en la investigación de resultados en detalle.

Para un excelente, a fondo, revisión de las herramientas de la vía, consultar:

Otra buena fuente de asesoramiento sobre análisis de vías, especialmente para aquellos que están familiarizados con el paquete R estadísticas es aquí.

Otras lecturas