Or: “A beginner’s guide to herding cats”.

Consider this scenario: you are an academic scientist, in a busy research institute and your boss is invited to edit a book, but declines due to pressure of work; then suggests that it would look good on your CV. You agree, it would look good on your CV, so you commit yourself to editing your first multi-author academic science book.

So why is that a problem?

Getting authors on board

You want the best people to write the chapters. You Google some big-name experts and invite them to contribute a chapter to your book. They almost all decline, or fail to reply to your email. But, somewhat to your amazement, one agrees. However, this paragon of science then never, ever replies to any future contacts. So, you lower your sights and aim for good scientists, but not Nobel Prize winners. 最后, you get enough authors together to write the chapters around the topic that the publishers have given you – phew!

Getting authors to agree a deadline

Assuming it’s not unreasonable, everyone is usually relaxed about the deadline set. However, the real challenge is:

Getting them to meet the deadline

- This should be easy, right? Scientists are grown-up, professional people. Aren’t they? 好, sort of. In reality, academics typically over-commit themselves, doing not only research and teaching, but also writing grant funding applications, papers, reviews, book chapters, etc, etc. After all, the scientific mission statement is “publish OR be damned.”

- As the deadlines go past – “wooshh”, like passing cars, half your authors have submitted their chapters, the rest not. Now another sticky moment arrives – these are meant to be cutting edge reviews. State-of-the-Art. But this delay now means that the ‘good’ authors work is rapidly reaching its sell-by date. You may have to go crawling back to them to ask for updates. Which they are usually not too unhappy about, but you hate the loss of face.

- One more thing that I forgot to mention; as the editor, you have to READ these chapters. Worse still, you are expected to produce cogent critiques – what the author needs to add, remove, expand or contract. Even if the topic is on the fringe of your main expertise.

What happens if authors go AWOL?

What do you do when one of your authors decides that they are NOT going to write their chapter? Not simply procrastinate, fail to meet deadlines, but stop all communication. Disappear off the map. So, now you’re stuck – find another author(s) – more delay – write the chapter yourself? – but it’s too far outside your own area of expertise. So, eventually, you find someone else. Which means yet more delay.

Writing your own chapter

Oh, yes, you forgot that you agreed to write one of the chapters yourself. Oops. Oh well, not a problem. Offer co-authorship to one of your PhD students – they’ll be falling over themselves to get another publication on their CV. Or maybe not: no, they are not interested after all; obviously suspecting (correctly) that your aim is to let them write the whole thing, then submit the chapter to you for a little light editorial polishing.

Pleading with the publishers for more time

- You now hold the dubious record for the longest gestation period of a multi-author academic book in human history, excluding the Bible.

- ‘Please, sir, I want some more.’

- The publishers are not impressed, but quietly resigned, telling you to go away and come back when you meet a new deadline.

Losing your marbles and giving up completely

It’s all taking SO LONG – too few authors have submitted first drafts of their chapters. You start to get desperate – the original deadline was so long ago that you’ve forgotten it – the “new” deadline is also now history. You consider giving the whole thing up – apologise to the authors and the publishers and say the book can’t be finished. But your co-editor and the authors who have delivered on time are indignant – naturally enough they don’t want to see their work wasted – and insist that you go back to the recalcitrant scientists with a big stick. How do you threaten authors with a stick by email? Or by phone? However, a combination of the metaphorical big stick, pleas for mercy and piling on the guilt eventually work and all the chapters are delivered! Hooray.

Hooray!

So, now, you’re on the last lap. Or the last dregs – the soul-destroying process of assembling the index and proofreading. Once, a sub-editor with a scientific background might have written an index, but not now. Academic publishers want their pound of flesh, so this task is delegated to authors and editors. Authors select keywords from their chapters, with varying degrees of enthusiasm or accuracy, then the editor attempts to assemble them into something useful to the reader. 最后, a draft proof arrives by email. You are now heartily sick of every word, but a final spurt of enthusiasm drives you on and the book is finished.

One more thing – did I forget? – you don’t get paid – but you are given a few free copies of your own book. Such fun!

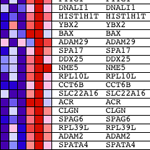

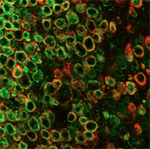

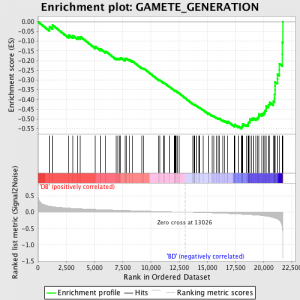

基因集富集分析的许多方法之一 分析基因表达 描述文件数据,并在所述 纸工人在Broad研究院.

基因集富集分析的许多方法之一 分析基因表达 描述文件数据,并在所述 纸工人在Broad研究院.