The Annual meeting of the British Society for Gene and Cell Therapy, as well as being aimed at the expert, included a day of presentations intended for students and the public. Aimed primarily at GCSE and A-level students, but open to all, this one day interactive event provided an opportunity to discuss and debate gene and cell therapy research with scientists, patients, journalists and clinicians, and to think about the impact that this research has on society.

The Annual meeting of the British Society for Gene and Cell Therapy, as well as being aimed at the expert, included a day of presentations intended for students and the public. Aimed primarily at GCSE and A-level students, but open to all, this one day interactive event provided an opportunity to discuss and debate gene and cell therapy research with scientists, patients, journalists and clinicians, and to think about the impact that this research has on society.

@NakedScientists Please ask followers to tweet genetics/gene therapy questions to our expert panel @_BSGCT #BSGCT #BSGCTPED 17th April

— BSGCT (@_BSGCT) April 15, 2013

First speaker of the day was Dr Tassos Georgiadis:

Curing Blindness with Gene Therapy

Dr Georgiadis told us about different forms of inherited blindness and explained how gene therapy works in the eye. Some therapies halt a disease that would otherwise get progressively worse and others may actually improve sight. The most awe-inspiring part of the whole talk was a short video ( you can watch it here – there is a 15 second advert first) showing how one person had his eyesight improved dramatically by gene therapy.

Next up was Dr Tristan (Tris) McKay:

What is Stem Cell Therapy?

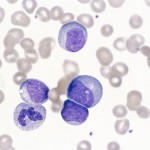

Dr McKay explained that not all “stem cells” were equal; the different types, embryonic, fetal, and adult, have subtly differing potencies to develop into the specialised cells in the body. He also talked about a recent development that has contradicted a previously long-held dogma that specialised cells, such as skin cells, cannot become stem cells. This breakthrough, allowing stem cells to be generated much more easily from adults, led to the discoverers, Sir John B. Gurdon & Shinya Yamanaka, being awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 2012. Anyone who would like to know more about Stem Cell Therapy could listen to the three lectures downloadable (for free) from iTunes U.

Stem Cell Therapy and Transplantation

Dr Emma Morris told us how she had asked her own children how best to talk about her work, on Stem Cell Therapy, with teenagers studying for their GCSEs or A-levels. Their answer was to do the same as she had done for primary-school children; the outcome was not patronising, but entertaining, enthusiastic and engaging. Dr Morris studies, and uses in therapy, the stem cells found in the bone marrow that can specialise as blood cells. She told us about how bone marrow transplantation was first tried in 1959, to cure five Yugoslavian nuclear workers whose own marrow had been damaged by a nuclear accident. Unfortunately this failed because the workers’ immune systems rejected the transplants. Since that time, as we have learned to control or avoid the problem of rejection, bone marrow transplantation has become a highly successful technique for treating cancers of the blood. And not only can we use transplants from an adult donor, but also stem cells from the blood of umbilical cords or even our own blood stem cells – after “filtering” out the specialised cells.

Dr Emma Morris told us how she had asked her own children how best to talk about her work, on Stem Cell Therapy, with teenagers studying for their GCSEs or A-levels. Their answer was to do the same as she had done for primary-school children; the outcome was not patronising, but entertaining, enthusiastic and engaging. Dr Morris studies, and uses in therapy, the stem cells found in the bone marrow that can specialise as blood cells. She told us about how bone marrow transplantation was first tried in 1959, to cure five Yugoslavian nuclear workers whose own marrow had been damaged by a nuclear accident. Unfortunately this failed because the workers’ immune systems rejected the transplants. Since that time, as we have learned to control or avoid the problem of rejection, bone marrow transplantation has become a highly successful technique for treating cancers of the blood. And not only can we use transplants from an adult donor, but also stem cells from the blood of umbilical cords or even our own blood stem cells – after “filtering” out the specialised cells.

Dr Morris also mentioned some of the more attention-grabbing experimental therapies such as building new tracheae with a plastic framework on which bone marrow stem cells can grow, given the right growth-stimulating factors, or “designer” stem cells programmed to attack cancer cells. Some of these approaches remain highly speculative and in many cases have only been tested in mice, nevertheless, they are promising.

Have to mention that the audience was not composed entirely of students, but also a few general members of the public and during one of the breaks I:

#bsgct met delightful lady in audience who had multiple myeloma & bone marrow transplant – should have been invited present patients' POV!

— Paul Denny (@pauldennyuk) April 17, 2013

The next presenter had a uniquely passionate point of view, because he was both a patient (with haemophilia) and a scientist; Dr Adam Jones:

Gene Therapy – A Patient’s Perspective

Dr Jones started by giving us a brief history of haemophilia – the earliest written record being in the Jewish sacred text, the Talmud, which dates back to between 200 and 500 AD. He then launched into a semi-autobiographical series of stories – he was a good story-teller – about life as a haemophiliac, required to take a drug, called Factor IX, in order to avoid bleeding to death. These stories were blackly comic and thought-provoking; particularly when he compared the cost of the NHS buying Factor IX for one person (£157,872 per year) with paying a Premier League footballer (~£250,000 per **week**)…

But what has this to do with gene therapy, you may be thinking?

Well, despite the existence of therapies for haemophilia, they are not a cure. Gene therapy is expensive, perhaps ~£30,000 per treatment and indeed may not be a permanent cure, but may need to be repeated once or twice per year. However, if such a therapy existed it would do two things:

- release haemophiliacs from the need for several injections of Factor IX per week into their veins.

- save money for the NHS.

Fortunately, research to achieve this goal is ongoing, with some early promising results.

The final speaker was Ed Yong, a science writer who left the lab after realising that it really didn’t suit him, because he enjoyed talking about science far more than doing it.

His topic was:

Beyond “The Gene for X”

Ed warned us that he was going to deviate from the main theme of the day and take us into the new territory of personal genome tests and the unfortunate tendency of the media to over-simplify genetics. He listed stories about genes that “cause” everything from our DIY skills, to risk-taking, being politically liberal, or even eating a whole bag of crisps. Of course, none of these are simple, deterministic Mendelian genetic “effects”. But these subtleties rarely get reported, or if they do, they are buried well down the published text. So, reader, beware.

In the area of personal genome tests, Ed related his experience with having his own genome tested by a company called 23andme – this threw up some strange results. Ed is of east-Asian origin and has black, ramrod-straight hair, but his genetic test results predict that he should have curly hair!

One of the most entertaining moments occurred when the PC temporarily froze and so Ed told the audience another story, about a girl called Lily with a mysterious disease for whom genome sequencing had offered hope for the future. This was a fascinating story of scientific discovery, yet tinged with an element of sadness because although the cause of Lily’s illness has been found, there is, as yet, no cure.

The final session consisted of the speakers and other scientists with expertise in stem cell and gene therapies, answering questions directly from the audience, or from tweets sent to #bsgctped during the day. There were some great questions e.g.

- “How does the way stem cell research is done vary between countries?” A: Significantly – regulations in UK are strict, but relaxed by comparison with the USA.

- “What A-levels do I need to study medicine at University?” A: the only subject that is obligatory is Chemistry, but another speaker also mentioned that a slow route, but possible at some Medical schools, allows you to study any combination of A-levels, then study whatever first degree course your heart draws you to, then go into medicine later.

- “How did the panel’s religious beliefs affect their science?” This drew a lot of very interesting replies…

This rounded up an entertaining and informative day and I would recommend it highly for science teachers or for GCSE / A-level students, especially if studying biology or for any member of the public, curious about this area of science, in future.

One Comment

Fantastic conference and public engagement day – well done to the speakers and organisers for putting on such a fabulous day. Hopefully we have inspired new generations of school kids into developing the medicines of the future!